The grip that led to Skip’s memorable 1951 Ryder Cup heroics

If there has ever been testament in golf to persistence and the age-old axiom that a proper grip is necessary for success, look back 70 years for the underappreciated story of Skip Alexander.

Alexander grew up in Durham, N.C., graduated from Duke University and claimed Pinehurst Course No. 2 and the 1951 Ryder Cup as his favorites – all within proximity to Golf Pride’s Pinehurst headquarters.

What transpired in the fall of 1950 and over the next 14 months should be recollected, especially since the Ryder Cup is scheduled for September 24-26 in Kohler, Wisc., at Whistling Straits when there will be lots of bluster about heroics and bravery but nothing like this.

Alexander was situated in the Duke Hospital in early 1951, amid 17 major surgeries lasting more than 50 hours. The doctor in charge of the case was Dr. Leonard Goldner, a budding orthopedic hand surgeon.

With third-degree burns over 70 percent of his body and a snapped left ankle suffered as the sole survivor of a September 24, 1950, Evansville, Ind., airplane crash, there were concerns about Alexander’s charred exterior. Goldner insisted it may be time to take care of his hands.

The hands are the soul of a golfer’s craft, connecting the body to the club with the essential grip fundamentals. Alexander’s large hands were disabled after he punched through an airplane door on fire, clothes and hair on fire amidst a blue cloud of fuel ready to explode, and prone on the ground 100 yards from the downed plane. Alexander would compare a first glimpse of his hands to “yellow molasses.” A St. Petersburg, Fla., writer described: “His hands were twisted so that his fingers stuck out at odd angles like the scarecrow’s in the Wizard of Oz.”

unprecedented surgery

Goldner explained that Alexander’s hands may require the amputation of pinkies and a portion of his ring fingers on each hand. But the doctor who was the same age (32), also a World War II veteran and an avid golfer met with some defiance.

“Isn’t there another option?” Alexander countered, in a recollection by Skip’s son, Buddy. “What I would like to do is to freeze my hands in a grip-like position. My sponsor, Wilson, sent me a gift with flowers of a short club with a grip on it. I would like for you to take that club into the operating room so you can understand how my hands need to clamp down on the club. Make it so I can grip a club again.”

The hands are the soul of a golfer’s craft, connecting the body to the club with the essential grip fundamentals

Goldner informed his surgery team to sterilize the club for the first procedure and four total major surgeries which took place on each hand over the next few months that permanently shaped them like a cupped ‘C.’

Medical records, released by Duke to the Alexander family for the first time in July 2021, indicate skin grafts, pin insertions, splints and casts were utilized as “… the patient was able to return to playing golf, and his record has been satisfactory,” an April 1952 report stated. The medical records contain a dozen fuzzy, black-and-white photos of Alexander grasping golf clubs as if it’s a Golf Digest gripping lesson.

Another remedy that allowed him to play on was grip manipulation. Both pinkies were 70 percent disabled, forcing him to switch from an overlapping to interlocking grip and to place his deformed left pinky off the end of the club. As a part of Alexander’s lifetime $2,500 annual sponsorship with Wilson, the manufacturer sent clubs with grips made as small as possible, often inverted with a skinny end and thicker down the shaft. They also realized Alexander liked to grind down the end of grips to better fit his hands, so there were occasionally messages such as “Good Luck” written on tape under the wraparound leather grips for Alexander to surprisingly discover.

THE CRASH

Alexander was a star in the making before his accident. Handsome, a long driver of the ball and personable, Alexander had won three times by age 32. Then came the tail end of the 1950 season.

Alexander finished sixth at the Kansas City Open on Sept. 24, 1950, but a rain delay pushed the round to later in the day and Alexander missed his commercial flight home. A plane summoned by the Civil Air Patrol, a civilian auxiliary to the U.S. Air Force, promised to get him to Louisville, Ky., that evening and onto a commercial flight to North Carolina so he could visit with his family before hopping to South America a couple days later for a well-paid golf tour with some professional cohorts.

A malfunction in the plane’s fuel tank necessitated an emergency landing in Evansville, Ind., but the plane never made the runway, crashing a mere 600 yards short. Alexander escaped the plane as the other three were gravely injured or trapped by debris. What Alexander met was flames, so he used the exterior door as a shield, and pushed on. As he lay on the runway and a passerby snuffed out his fiery body, the plane’s fuel tank exploded to kill the remaining inhabitants.

Alexander’s large hands were disabled after he punched through an airplane door on fire, clothes and hair on fire amidst a blue cloud of fuel ready to explode, and prone on the ground 100 yards from the downed plane.

There were estimates that Alexander had a 15 percent chance of survival. His crushed left ankle was repaired, but not fused because that wouldn’t allow Alexander to finish his golf swing, leaving him in pain for the rest of his life. Numerous skin grafts were required over five months spent in two hospitals.

“They primarily wanted to save his life and probably didn’t think they would be able to do that at first,” daughter Bunkie (Alexander) Tate said. “But Dad was already thinking beyond that. He was a very, very determined human being, even before the crash. He put his mind to it and willed his way through that.”

Three months in Evansville allowed him to get out of the woods and be in shape for a transport home by year’s end for further surgeries. By August 1951 he was back playing on the PGA Tour to secure his spot in the early November Ryder Cup at Pinehurst.

Skip’s heroic return to the Ryder cup

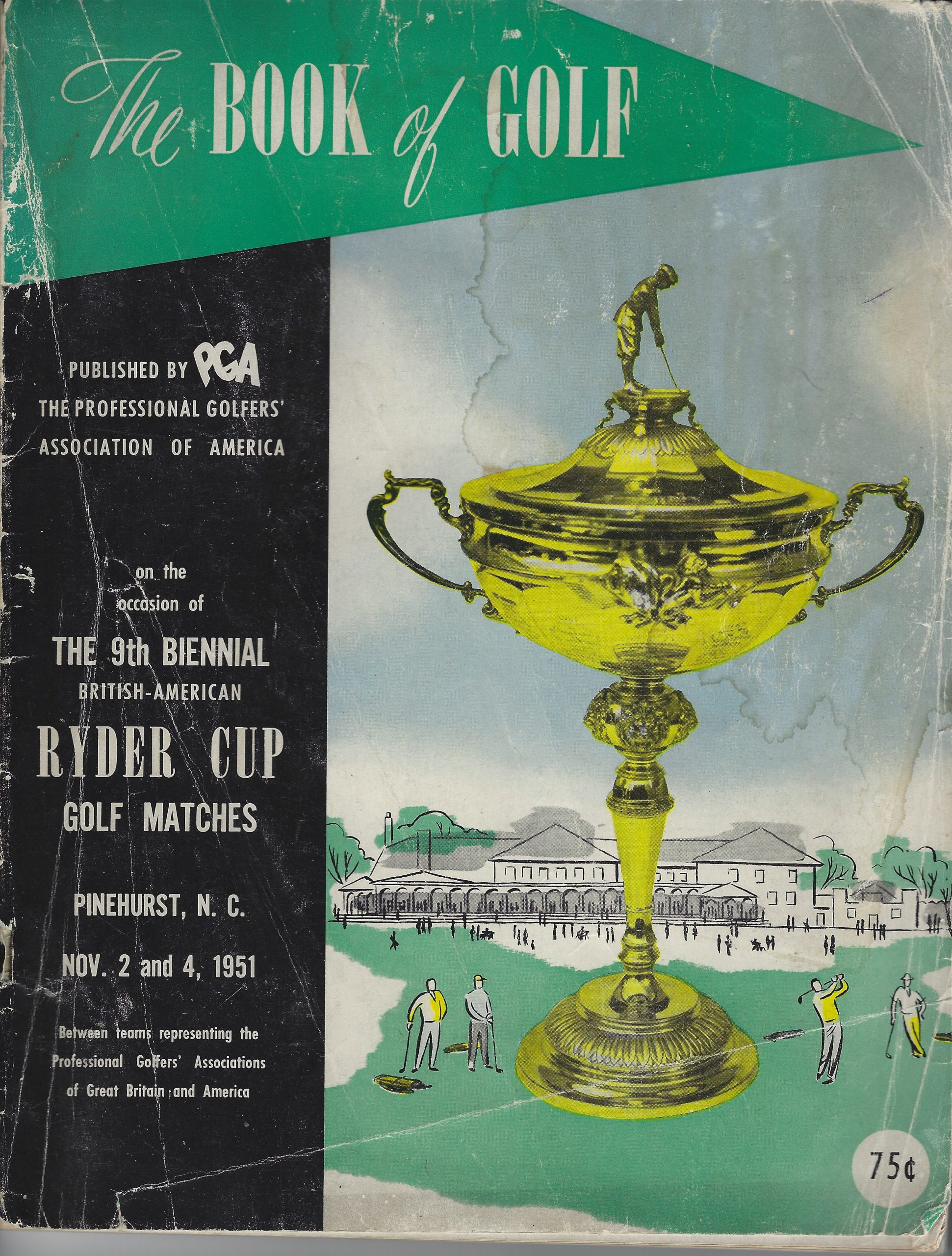

The 1951 Ryder Cup was nothing like its current circus atmosphere. There were just two days of matches in the first week of November, one devoted to team play and the final day to singles. The gathering was so low key that the North Carolina vs. No. 1 Tennessee college football game in Chapel Hill held precedence as the golfers took a break on Saturday.

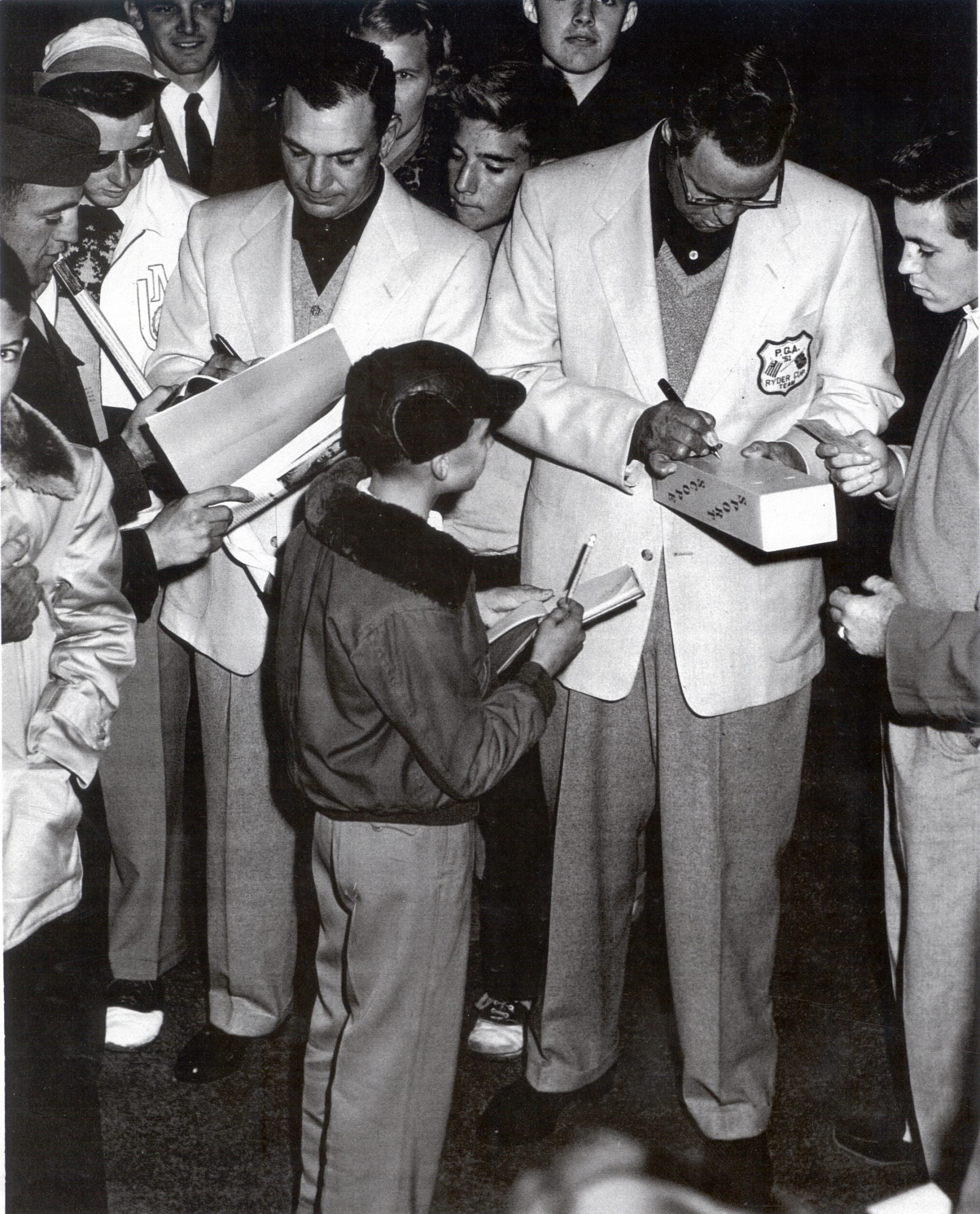

Sam Snead, the U.S. playing captain, penciled in Alexander for singles after sitting him out for the team matches, surprisingly to do battle with Great Britain’s No. 1 player, “Gentleman” John Panton. With doubts about his durability, Alexander built a 5-up lead at the lunch break. But the cotton gloves Alexander wore on both hands for protection had to be replaced because his hands were bleeding, the towels on his golf bag were bloody and his usual left ankle limp worsened. As Alexander’s lead grew to 8-up by mid-afternoon, he still thought, “Every time I played a hole, I wondered if I could play the next.”

“As Dad liked to tell the story over the years, No. 11 at No. 2 comes back fairly close to the clubhouse, his hands were bleeding, he was out of dry towels, so ‘I had to dust his ass right there’,” Buddy Alexander recalled.

Alexander called it the “greatest day of my life.” He was but 3-over par in the 8-and-7 victory that remains among the biggest victories in 36-hole singles history. The U.S. team won 9½-2½, so it wasn’t a decisive match. Yet, Alexander’s personal heroics are underplayed, often reserved as a mere footnote in Ryder Cup annals.

his legacy lives on

Alexander continued to play occasionally on a national level but never fulltime after 1951. He had always wanted to be a club professional, so he served 34 years at St. Petersburg Country Club, retiring in 1985. He received a plethora of sports survival awards and places in Halls of Fame. There’s even the possibility of a movie being produced in the next couple of years.

Alexander’s golf was lived through others. Buddy won the 1986 U.S. Amateur, earning a spot in the 1987 Masters paired with defending champion Jack Nicklaus and with his father attending.

After Skip died on Oct. 24, 1997, at age 79, his golf spirit remained. Buddy’s University of Florida men’s golf team was inspired by the 2001 NCAA Tournament site at the Duke Golf Club, a couple miles from where Skip is buried, as Buddy visited each morning, and the Gators won the title.

Finally, Tyson, Skip’s grandson and Buddy’s son, was getting closer to earning his PGA Tour card as the 2021 Korn Ferry Tour season wound down. Even though the 33-year-old fell just short of his card for 2022, the final event in early September was held in Evansville, Ind., where 71 years ago an Alexander’s life changed and another carries the mantle forward.